Edmund S. Phelps (new Keynesian) was awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize for the contribution of intertemporal tradeoffs in macroeconomic policy. The intertemporal tradeoffs are from mainly two parts. One is the tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. The other is about capital accumulation and economic growth.

Expectations-Augmented Phillips Curve

In the early 1960s, economists believed that the tradeoff between unemployment and inflation was stable, as the Phillps curve. In the late 1960s, Phelps challenged this view by considering expectation about future inflation.

One of Phelps’ major contributions to economics was the insight he provided on the interaction between inflation and unemployment. In the Expectations-Augmented Phillips curve, he combines current inflation with future inflation and unemployment.

Previous economists including Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises argued that people adapt their inflation expectations to account for the effects of expansionary monetary, Phelps is recognised as the first to formally model this phenomenon.

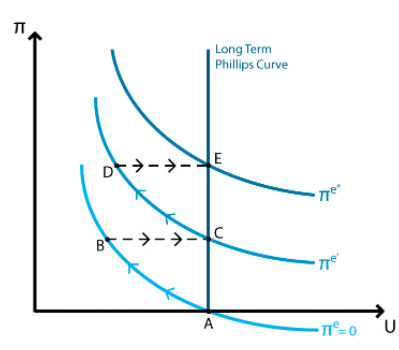

In the first period, the government decides to conduct an expansionary monetary policy, inflation would rise and unemployment would fall, based on the simply Phillps curve. However, a second or third time comes, agents would be quick to associate higher inflation with rising salaries in their expectation adjustment. That would anticipate that inflation would drain their purchasing power accordingly, and the monetary policy would have little effect.

A better way of helping low-skill workers is to expand the earned income tax credit, making it more available to more workers. This way would be more superior to the minimum wages.

The long term Phillips curve is vertical because of the potential GDP. The price level keeps increasing as the expansionary monetary policy. The unemployment rate decrease when the policy is released but the effects diminish in the long run.

Intuitively, if the Federal Reserve increased the money supply at a rate that caused a 5% inflation rate, then, with this higher inflation rate, wages offered would be higher than expected also. Unemployed workers looking for work would see wages that they would mistakenly think were higher in real terms and would, therefore, accept jobs at these wages sooner than otherwise. Millions of unemployed workers taking jobs just a few weeks earlier would result in a lower unemployment rate. Then, however, workers’ expectations would be adaptive; that is, they would adjust to reality. They would realize that the wages weren’t as high in real terms as they had thought, and some would quit and look for more lucrative work, thus slowly raising the unemployment rate. In other words, policymakers could temporarily reduce the unemployment rate by making inflation higher than people expected, but they could not achieve a long-run reduction in unemployment with an increase in inflation. In the long run, then, there is no tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. This striking finding is now mainstream economic wisdom.

Related to Robert Lucas’ work: Lucas emphasised “rational expectations” rather than “adaptive expectations”. The idea is that people would try to anticipate the future based on how the monetary authorities had acted in similar circumstances in the past. In this case, Lucas found even stronger results. Lucas’s model implied that the only way that policymakers could use monetary policy to affect the unemployment rate was by being unpredictable.

Golen Rule

Phelps developed the golden rule of the intertemporal tradeoff between present and future consumption as it relates to capital investment and growth. Phelps’s model formally defines the rate of savings and investment that is necessary to create the maximum level of sustained consumption across successive generations.

In the early 1960s, he derived the “Golden Rule” of capital formation. The rule is that if one’s goal is to attain the maximum consumption per capita that is sustainable in the long run, annual saving as a percent of national income should equal capital’s income as a percent of national income.

In the late 1960s, Phelps did further work in this area with Robert Pollak. They argued that the government should force people to save more than they wish, on the grounds that people put too little weight on their children’s well-being. It seems that the political system, though, does the opposite, especially at the federal level. The federal government taxes the politically powerless younger generation to subsidize—through Medicare and Social Security—today’s politically powerful elderly.

Considering the current economy in China!